EDITORIAL

Ti Similla Vol. III, No.2, August 1972, p. 1.

The Ti Similla August 23,1972

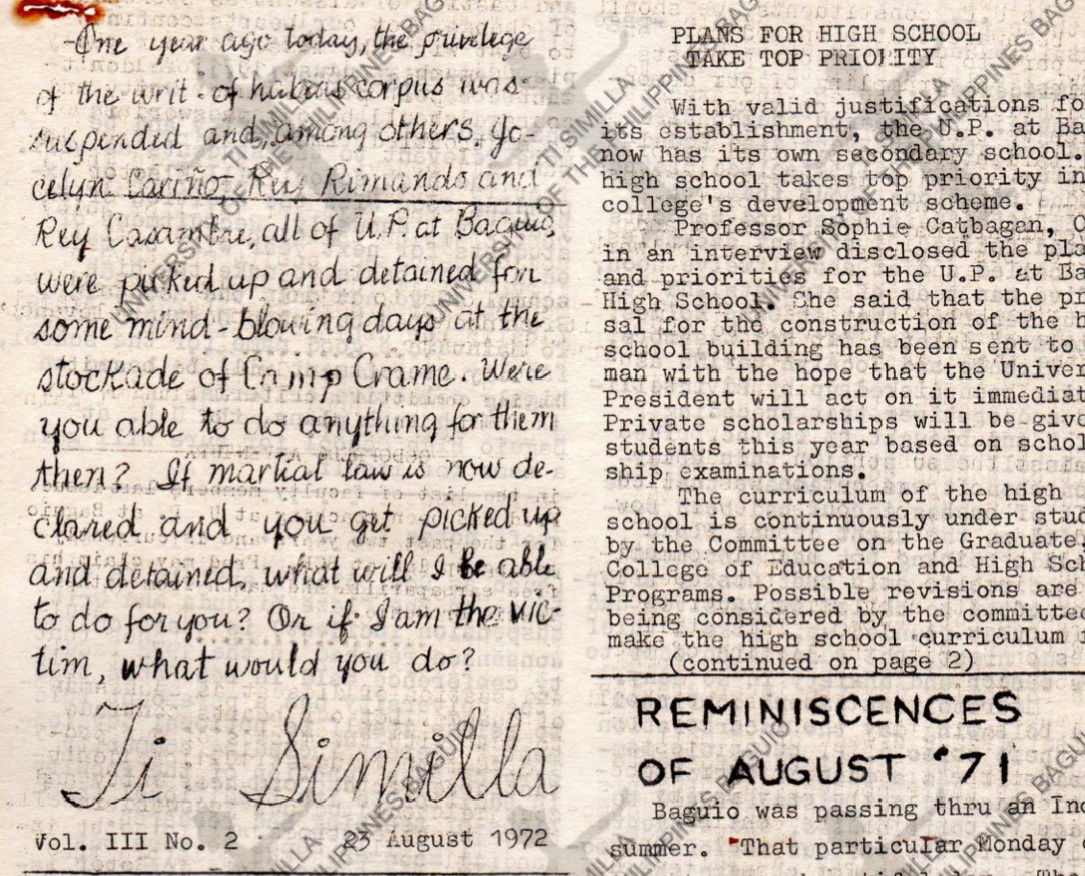

“One year ago today, the privilege of the Writ of Habeas Corpus was suspended and among others, Jocelyn Cariño, Rey Rimando, Rey Casambre, all of UP at Baguio were picked up and detained for some mind-blowing days at the stockade of Camp Crame. Were you able to do anything for them then?

If Martial Law is now declared and you get picked up and detained, what will I be able to do for you? Or if I am the victim, what would you do?”

This hand-written note was located at the top of the cover page, written in cursive. There were two questions that drew my attention: “What will I be able to do for you? and “What would you do?.” After reading this issue of Ti Similla, these two questions never left me. Martial Law was lifted by former President Ferdinand Marcos in 1981. In 1986, Corazon C. Aquino assumed presidency and a series of Philippine presidents assumed position from 1986 onwards. Our country had four presidents, and one whose term ends next year. It has been 49 years since Martial Law was declared but the hand- written questions in this Ti Similla issue remain unanswered.

This current issue of Ti Similla bravely confronts these questions. Staying true to the tradition of critical reflections, we bring you back to 1972 alluding to the decades that followed. Two social commentaries are presented in this issue: Ruel Carricativo’s The Dictator’s Handbook: Marcos, Duterte and Martial Law and Orville Tatcho’s The Need for Rhetorical Literacy in the 2022 Philippine Election that speak of rhetoric: the rhetoric of authoritarian positioning to control society and the rhetorical literacy that should be consequential to informed choices for the 2022 elections. Both commentaries take us back to 1972 and discuss the similarities in the rhetorical game of former President Ferdinand Marcos and the current Philippine President. Ruel D. Caricativo unfolds a “dictator’s manual,” showing the eloquent orchestration on authoritarian ruling. Orville Tatcho expands rhetorical language design that perpetuates historical revisionism and false claims on “change,” “discipline” and “development.”

What will I be able to do for you? was a hanging question—a challenge by Ti Similla Editors in 1972. I read this as a question on my contribution in making people remember the truth about the Martial Law period. It is my duty then not to trivialize and sanitize the narratives of oppression. It is my moral obligation to make noise and re-tell these stories to my students- -to make them understand that what they read, what they hear and what they see are all part of an illusory rhetoric to make us believe that the Martial Law years were for the good of many. It is within the scope of my capacity to correct and to explain that what happened before can and is happening today.

It is owning up to correcting this rhetoric that makes it imperative for me to communicate to my students that the names of rulers may change but the agenda to curtail freedom remains. It is taking responsibility in making my students understand that Martial Law and the military authority for civilian rule have evolved into names such as Anti-Terror Bill, the suspension of the bilateral agreement between the University of the Philippines and the Department of National Defense, extra-judicial killings, among others are versions of oppression to embed fear that will silence us.

This is what I can do. It is within my scope as a faculty to make it comprehensible for everyone that the acts of historical revisionism are ways for us to forget, to erase the atrocities done to many, to disempower memory-making and orchestrate the non-naming of oppression. And, in doing so, for us to remain silent, and worse to remain neutral.

What will you do? is a question etched in the August 23, 1972 issue of Ti Similla. I ask the same question. And for those of you reading this, do not be weary of this struggle. The Editors of Ti Similla ended this issue with these typewritten words in 1972, p. 2, signed by pk Botor,

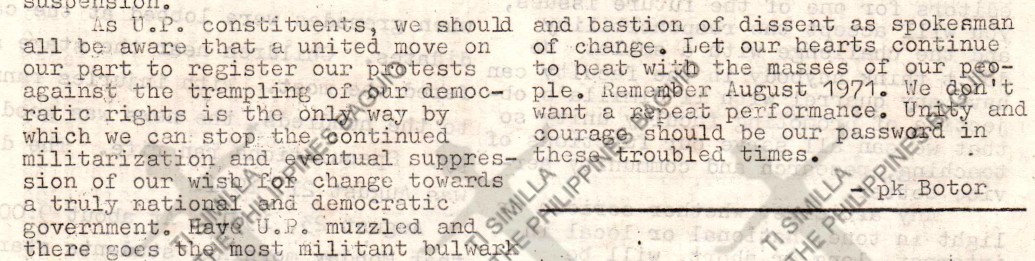

“As UP constituents, we should all be aware that a united move on our part to register our protests against the trampling of our democratic rights is the only way which we can stop the continued militarization and eventual suppression of our wish for change towards a truly national democratic government…have UP muzzled and there goes the most militant bulwark and bastion of dissent as spokesman of change. Let our hearts beat with the masses of our people. Remember August 1971. We don’t want a repeat performance. Unity and Courage should be our password in these troubled times.”

As fierce as these typewritten words are, feel the fire of these encoded sentences. I WILL REMEMBER AUGUST 1971. I WILL REMEMBER THE YEARS AFTER 1971. I will never cease to speak of this continuing oppression. I will never forget to speak for the disenfranchised. The questions “What will I be able to do for you” and “What would you do?” will be repeatedly asked of us until we truly achieve democracy.

Ti Similla Vol. III, No.2, August 1972, p. 2.

COMMENTARY

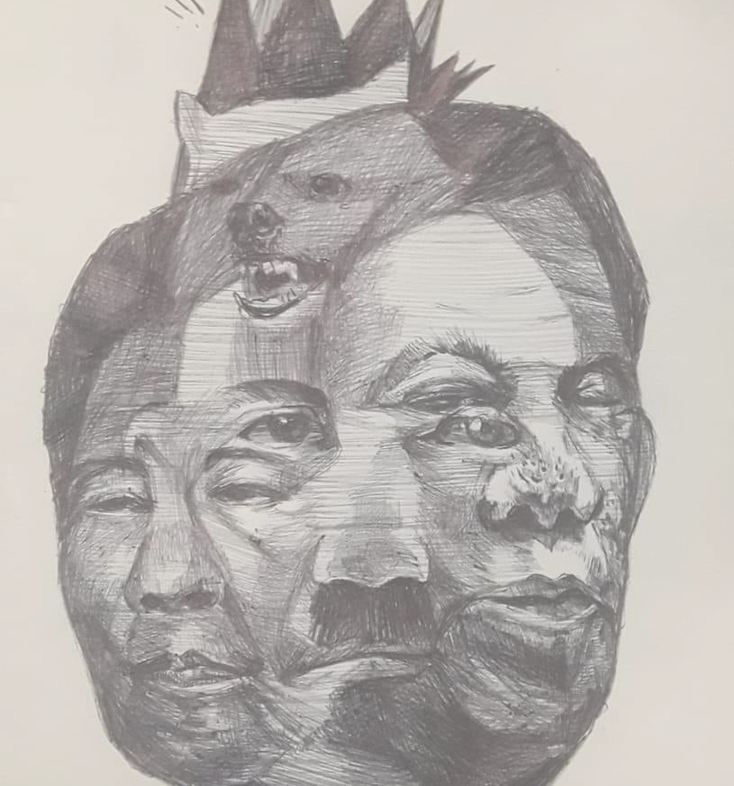

“Marcos, Duterte,Hitler, Tuta,” ballpoint on paper

Artist: Joseph Luigi Almuena

The Dictator’s Handbook:

Marcos, Duterte and Martial Law

by Ruel D. Caricativo

“Dictators tend to share patterns of rule, or in this case, a handbook… but they also share the same fate, and the fates of tyrants are always decided by the people.”

On the evening of September 23, 1972, former President Ferdinand Marcos announced in a televised broadcast that he had declared martial law, also known as Proclamation 1081, two days before. Of course, it was never just a declaration. Marcos imposed military rule against the toiling masses of Filipinos. More than four decades later, President Rodrigo Duterte has relied on a de facto martial rule across the country to impose his anti-people policies.

The similarities between these two regimes are undeniable; dictators may have emerged differently, owing to different circumstances, and they almost always enforce the same kinds of policies. In other words, dictators rule by the same metaphorical handbook. This brings us to raise questions about that oft-used remark: whether history tends to repeat itself, “first as tragedy, then as farce”.

Step 1: “Wall of silence”, or repression vs. mass media, freedom of expression. Dictators dislike dissent and critical thinking. Values they usually target in a democratic society involve freedom of expression and dissenting opinions provided through mass media institutions.

The imposition of martial law was so precisely calculated it was as if a thief came into the night undetected. By the early morning of September 23, 1972, the then-Philippine Constabulary (PC) took control of Metro Manila. They set up military checkpoints and roadblocks, and the Batasang Pambansa was padlocked. Over the next few hours, “some 8,000 individuals – senators, civil libertarians, journalists, students and labor leaders, and even scions of a few of the country’s elite families – had been arrested and detained without charges in a makeshift concentration camp in Camp Crame”. This was immediately followed by the forcible takedown of mass media institutions and their owners by virtue of Letter of Instruction No. 1. They were eventually replaced with Marcos’ cronies to control information channels through the Department of Public Information.

And what did President Duterte learned from the Marcos dictatorship? The first few months of his regime saw the relentless attacks against media institutions, ranging from distasteful remarks to downright misogynistic comments against journalists. Although the president seemed to have taken every criticism as a personal slight, there was a high possibility it was his administration’s modus operandi to silence critics of his national security as well as economic policies.

Step 2: “Shock and awe”, or militarization, state terrorism, and human rights violations. Dictators like “peace”, but it is the kind of peace described in Lino Brocka’s Orapronobis: “tahimik sa sementeryo.” Aside from silencing oppositionists and dissenters, dictators also weaponize the law. Then, they resort to drastic measures: arbitrary arrests and detention, torture, enforced disappearances, and state-sanctioned killings.

The reign of terror did not spare the Cordilleras. On April 24, 1980, Macli-ing Dulag, the staunch leader of the Kalinga-Bontoc mass movement against the proposed Chico River dams, was murdered by PC operatives led by Lt. Adalem.

Harassment, torture, “hamletting”, and “salvaging” haunted communities across the region. Military operations were carried against those who resisted destructive projects, one of which was the logging concession carried out in southern Abra by the Cellophil Resources Corporation, which was owned by another Marcos crony, Herminio Desini.

Around April of 1983, elements of the 623rd PC led by Capt. Berido swooped down on Beew, Tubo, Abra, and massacred innocent civilians. The father of one of the victims painfully recounted the events: “I saw my daughter come out carrying her daughter and after a while, one of the soldiers approached Josefina and hit her on the head. She cried out in pain and fell to the ground, her child falling beside her. Another soldier hit her on the face, and still another soldier came and stepped on her stomach. In great fear of what I just witnessed, I ran back to Lidao and there I was told later on that the houses at Patuk-ao were set on fire by the soldiers”.

Step 3: Reward your cronies; then, lather, rinse, repeat. When Imelda Marcos was asked then why many of their relatives came to acquire so much wealth during the dictatorship, she had the audacity to respond, as she only could: “well, some are just smarter than others”. This best exemplified the cronyism that the Marcos family unleashed throughout their twenty-year reign. When Duterte assumed the presidency, he vowed to destroy corruption and the oligarchs. To some extent, he did. Remember Roberto Ongpin? At some point, Lucio Tan; later, the Lopezes. Then it turned out, he would prop his own oligarchs.

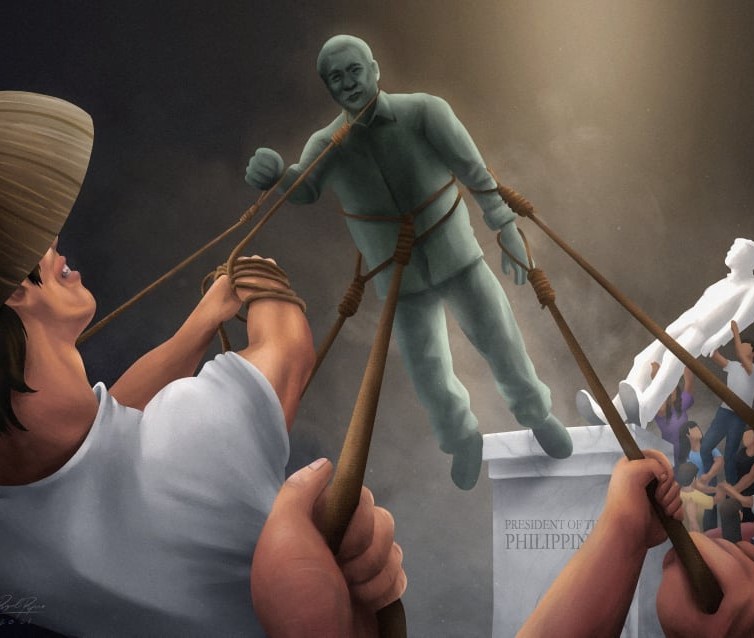

It would be a disservice to rigorous historical research to claim that all dictators, and in this case Marcos and Duterte, are the same. There were similarities, but differences in their regimes also abound. The point here is that dictators tend to share patterns of rule, or in this case, a handbook. But they also share the same fate, and the fates of tyrants are always decided by the people. Whichever way dictators tried to whitewash their legacies, the people will not be easily duped “for it is easy for force to acquire a title, but not for a title to acquire force”. Repression will always breed resistance.

Untitled

Artist: Raphael Reyes, BA Fine Arts 2nd year student

“Rhetorical literacy challenges us not only to delineate information from misinformation but also impels us to think through the motivations and impact of rhetoric.”

The Need for Rhetorical Literacy in the 2022 Philippine Elections

by Orville B. Tatcho

When I defended my dissertation which dealt with three case studies of political rhetoric and discourse in the Philippines since 2016, I proposed rhetorical literacy as a concept that voters and citizens must learn to make informed decisions in the forthcoming election. With similar goals to media and information literacy, rhetorical literacy can be a skill set or a range of practices related to the critical evaluation, analysis, creation, and reception of rhetoric. While rhetoric is a fuzzy term with often negative connotations, it can be defined as the study and art of speaking and writing effectively. Rhetoric is a way of communicating persuasively through strategies that make a message compelling as it appears in various media. Rhetorical literacy is then based on the critique and analysis of persuasive messages and discourse. It can be part and parcel of media and information literacy as rhetoric appears in every medium and is encoded as a message or ‘information.’ However, what would set rhetorical literacy apart from media and information literacy is its specific attention and commitment to understanding argument.

Ideally, an argument is a claim backed by proof and evidence. It is a reason offered in support of a position. It can also be a reason to negate a proposition (i.e., counter-argument). Rhetorical literacy teaches us to be critical of arguments in general and to interrogate mere claims masquerading as arguments (e.g., “pseudo-arguments”). So, when Duterte claimed that the Philippines is becoming a ‘narco state’ or when Marcos declared martial law in 1972 supposedly as a response to political instability brought by rebellion and secessionist movements or “anarchy,” rhetorical literacy dictates uncovering the facts behind these ‘arguments.’ What proof or evidence were offered in support of these claims? What backing or support make these claims believable?

An important skill in rhetorical literacy is critical research. Critical research means going to primary sources; identifying credible, authoritative, and scholarly sources (also a necessity in media and information literacy); and scrutinizing fallacies, inconsistencies, or tensions in arguments. Fact- checking can be an important element in rhetorical literacy but in cases where the facts are not always clear-cut, rhetorical literacy still offers an advantage. When we hear slogans such as “change is coming” or “sa ikauundlad ng bayan, disiplina ang kailangan,” rhetorical literacy challenges us not only to delineate information from misinformation but also impels us to think through the motivations and impact of rhetoric. Rhetorical literacy asks, why are Duterte and Marcos using ‘change’ and ‘discipline’ as themes, respectively? For whom is Duterte’s ‘change’ proposed and against whom is it positioned? What kind of ‘discipline’ is Marcos proposing and what were its consequences? Through critical research as a necessary condition for rhetorical literacy, questions like these can be raised and hopefully, answered.

The term ‘rhetoric’ in rhetorical literacy might be a misnomer because it suggests that the be-all and end-all is understanding rhetoric or argument. However, rhetoric or argument is only the starting point. It does not signal the end of the discussion. Once we have clearly identified the specific rhetoric or argument in question, a range of issues becomes visible. In the 2022 Philippine election, we should therefore be mindful of the kinds of political rhetoric that will dominate our digital and political spheres. As a practice in rhetorical literacy, we should ask: Has this rhetoric been used before? By whom, for what purpose, and at what cost? As rhetoric is consequential, what is the impact of a kind of rhetoric to collective perceptions and experiences? And as rhetorical literacy can go beyond rhetoric, we can also inquire into how rhetoric is socially, culturally, politically, and historically shaped; how its currency and pitfalls can be drawn from surrounding structural issues; and how rhetoric can be reimagined and recreated to serve the values of truth, freedom, and justice. In the end, if rhetorical literacy is to serve its purpose, then it must commit to the attainment of the said values.